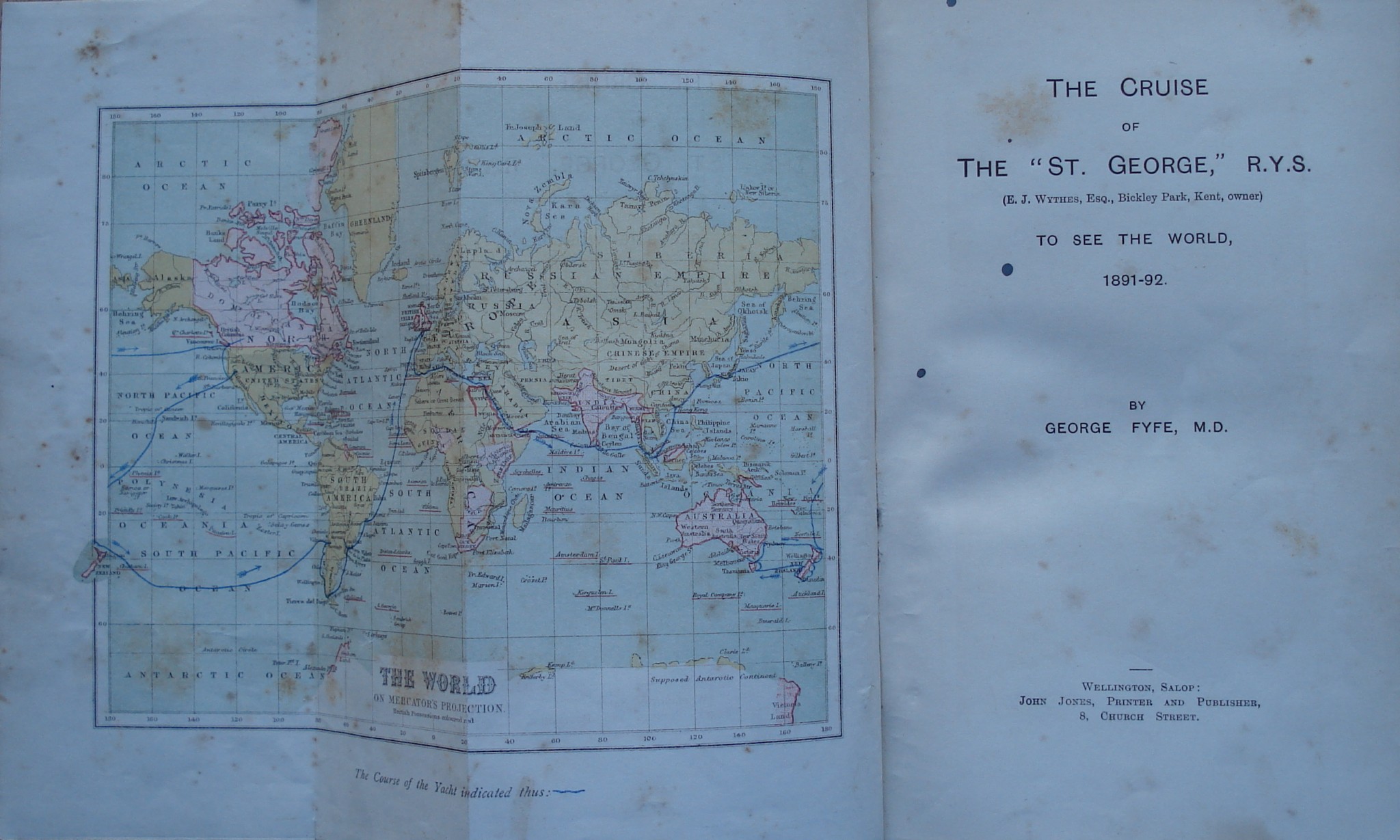

The Cruise of the St. George R.Y.S. to See the World

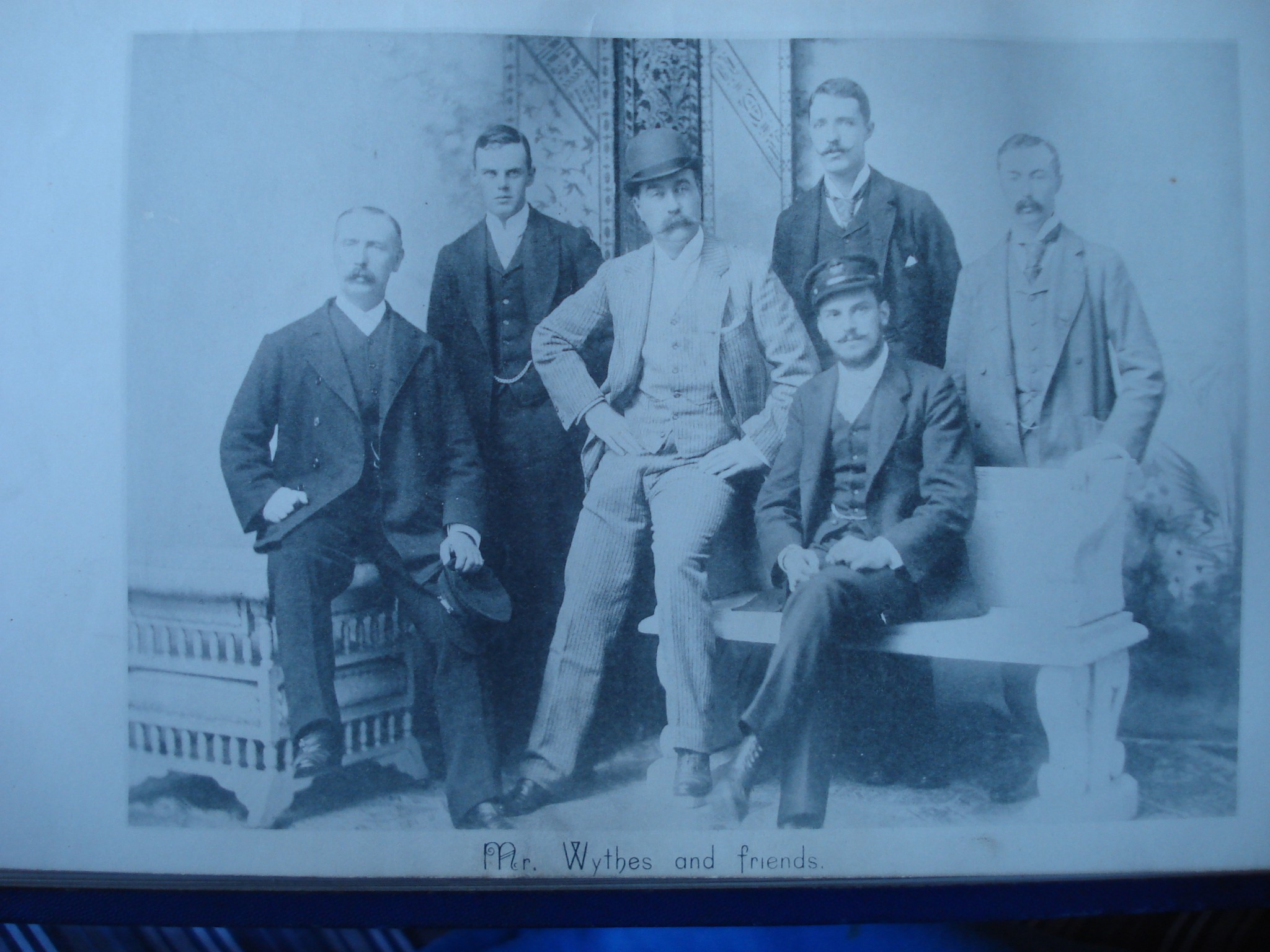

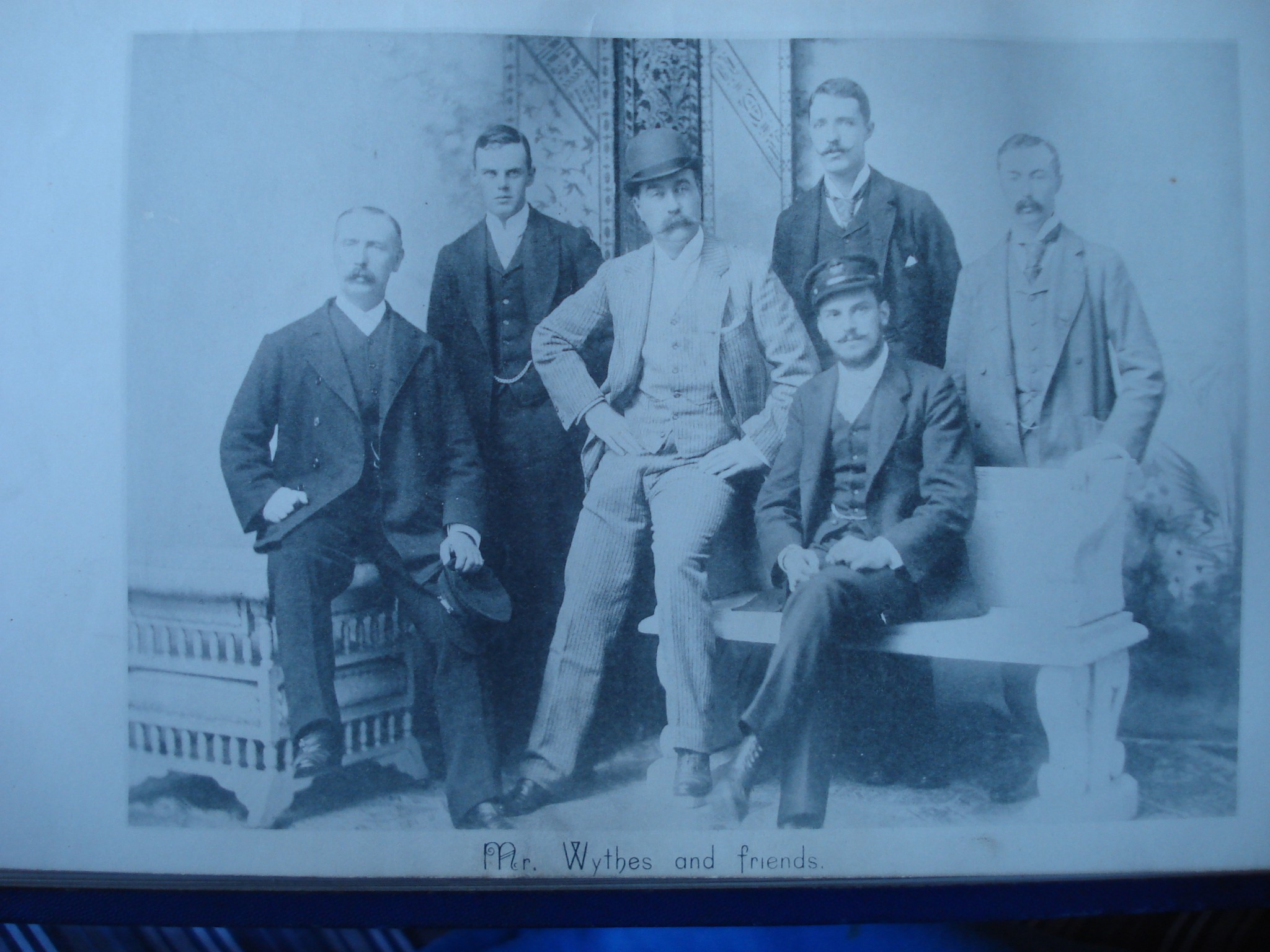

In 1891-2 one of the Squadron’s youngest Members, Ernest Wythes (1868-1949, RYS 1890-1949; Fig. 4), sailed around the world in his yacht St George. He was the son of George Wythes, who built railways in southern England with Thomas Brassey. Ernest was the grandfather of Mary Codrington, wife of The Hon. Robert Boscawen (RYS 1953-2013), who said that Wythes built the yacht ‘for something to do when he came down from Oxford’.

George Fyfe MD, the ship’s doctor, wrote a vivid account of the voyage, The Cruise of the St. George R.Y.S. to See the World (1893). This is his description of the ship:

‘The St. George is a three-masted auxiliary-screw steam yacht, and next to the Royal yachts is one of the largest and finest of the Royal Yacht Squadron, of which her owner is a Member. She was built at Leith, by Ramage & Ferguson, from the design and specifications of a first-class yacht architect (Mr. Storey) for her owner’s use … and has cost about £50,000. The predominant idea in her construction has been to combine strength and sailing qualities and special adaptation for navigation in distant seas, with elegance of yacht-like symmetry, and every home-like convenience and indeed luxurious comfort for the sea-farers aboard of her. The St. George is a hundred and ninety-two feet long and thirty-two feet beam, 1,000 tonnage, double-bottomed of teak and steel, first-class engined, and with everything in duplicate in case of break downs where repairs could not be effected; capable of steaming twelve knots an hour and of doing fifteen under canvas, for which she is specially rigged with arrangements for feathering her screw to favour her sailing speed ; electric lighted all over and electric search light if at any time needed. As to our cabins they are like elegantly upholstered bedrooms, ten feet high and nearly twelve feet square, with marble baths and hot and cold water arrangements. The saloon is thirty feet wide, well-lighted and ventilated, with open fireplace and overmantle, richly furnished, decorated and upholstered; has organ, piano, and well-selected library, chiefly travel, science, and fiction; as well as ample lounging and writing conveniences. The reception and smoking room on the deck is in keeping with the saloon, and forms an elegant and luxurious lounge for wet days and evenings… As to what I have jocosely called our ‘live stock’ there are fifty-three all told, consisting of thirty-seven A.B.s and ship’s officers, nine in the steward’s department, and seven gentlemen including the owner and myself. Our table is an exceptionally excellent one in viands, wines, beverages, &c., as well as in the no less important matters of cooking and waiting. (Fig. 5)

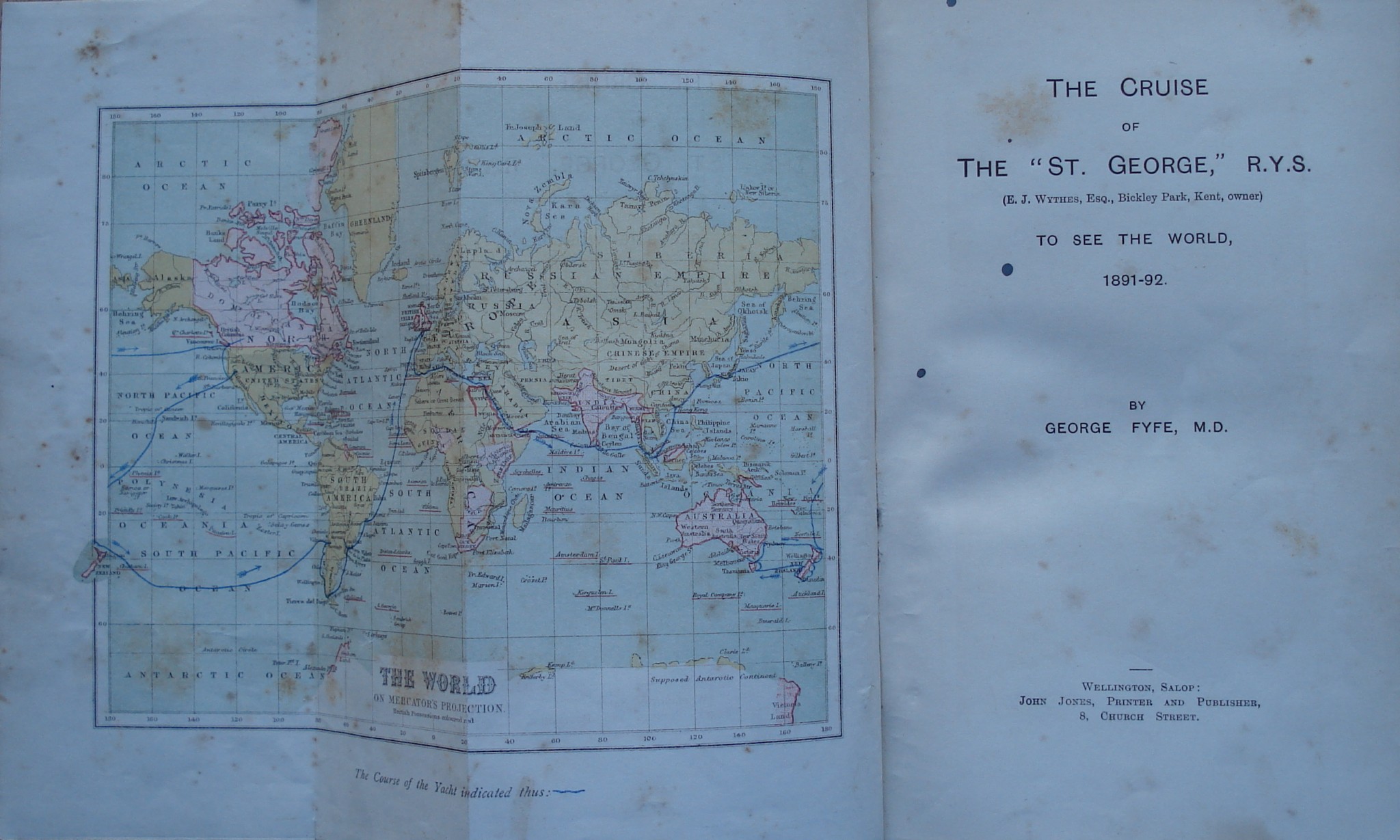

With 130 tons of coal on board they sailed from Southampton on Monday 19th January 1891. Their initial high spirits took an early battering from a three-day ‘duster’ in the Bay of Biscay, with storm-driven seas reducing everyone to a ‘limp and woebegone’ state. The doctor concludes, ‘I have lost all faith in medicinal remedies for sea-sickness, having tried several to no purpose — such as sodium bromide, cocaine, antipyrin &c. Some mitigation of one’s miseries, however, may be derived from lying flat on your back, and living on dry biscuits and cold water, and probably, after the stomach has become settled enough to retain it, a glass of champagne or brandy-and-soda water may be found useful as a pick-me-up.’

Finding calmer weather along the coast of Portugal, they sailed on to the Mediterranean, thence to Aden, Ceylon and the Far East, continuing to Vancouver, Fiji, Wellington, Sydney, Valparaiso and Cape Horn, returning to Southampton on 2nd November 1892. (Fig. 6)

The doctor was a learned and precise observer, interested in the flora, fauna, geology and weather of each place, as well as the character of the people, their history, culture and economic circumstances – and of course their diet and state of health.

In both Singapore and Hong Kong he was astonished by the wealth and vigour of great port cities created a few decades before from fishing villages. This moved him to a complacent reflection on the greatness of the British character:

‘Looking at the scene around and beneath me I could not help thinking what a wonderful race we Anglo-Saxons are, that by dint of our inherent qualities of energy and industry, intelligent enterprise and commercial sagacity, we should have been able to achieve such marvellous results in so short a time as fifty years; and that this youngest and most easterly of Her Majesty’s possessions should have thus become one of the largest shipping and commercial centres in the world. Fifty million pounds a year of trade with China goes through it, and nearly the whole of it is in British hands.’

The visitors were fascinated in a different way by Japan, which had been almost completely shut off to foreigners until 1853. Wythes allowed the inhabitants of one Japanese seaside community to come on board the yacht and look around. Dr Fyfe was surprised that the locals showed no inclination to steal any of the objects in the cabins and saloons – ‘which is more than could be expected from a promiscuous crowd of our own countrymen under similar circumstances.’

One night, shortly before leaving Japan, the owner decided to give the people of the port of Miwarra ‘an exhibition of the illuminating powers of the search light’. This technological display ‘greatly delighted them as they cheered most lustily at every fresh sweep it made. Mr. Wythes manipulated it himself and produced some very fine effects in the scenery behind the town and round the bay. Perhaps the limited area of the bay, with its environment of hills, the clearness of the air, and the darkness of the night, all helped to give increased potency to the electric luminant, for whatever it was thrown upon came out with a distinctness of definition that could not be surpassed by the brightest of moonlight.’ Everyone on board seemed caught up in the magic as the spotlight picked out ‘the hamlets in the valley, the windings of the streams, the streets of the town, with the groups of gossipers at the doors of the houses, the fore-shore and the landing quays, crowded with spectators looking towards us, the ships in the harbour, with their ropes, spars, names, displacement gauges, and the occupation of the men on board, and … the strange and unexpected sight of quite a large number of small boats, being rowed about the harbour in the dark, some containing both men and women, others women only; probably they were indulging in a Japanese aquatic equivalent to an evening stroll.’

The book is a succession of such exotic scenes, an eyewitness account of travelling on the frontier between the developed and undeveloped worlds at the end of the 19th century.

***

Return to the Appendices